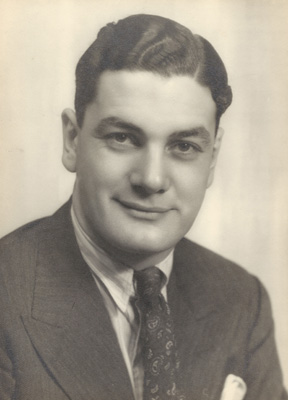

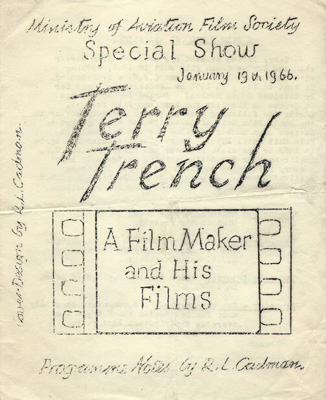

TERRY TRENCH

Documentary film maker

My father Terry Trench (1917-75) was a documentary film maker. He worked on about eighty-five films between 1935 and 1973, starting as an assistant cutter, and later working mainly as the editor, but sometimes as script writer or associate producer. |

|

|

Assistant cutter in the 1930s It is as an assistant cutter at Elstree that Terry Trench seems to have started his film career. He worked as an (uncredited) assistant cutter under the editor James Corbett on the musical comedy Music Hath Charms (1935) [70 mins], directed by Thomas Bentley, with music by Henry Hall, Mabel Wayne, Desmond Carter and Collie Knox. The film features Henry Hall and the BBC Dance Orchestra. This was an Associated British Picture Corporation Ltd film, made at Elstree, London. Wikipedia: Music Hath Charms Watch a clip from Music Hath Charms on YouTube: Just Little Bits & Pieces: Henry Hall & The BBC Dance Orchestra Terry Trench worked again as an (uncredited) assistant cutter under editor James Corbett on the feature film Ourselves Alone (1936) [68 mins], another Associated British Picture Corporation Ltd picture, directed by Brian Desmond Hurst (and Walter Summers), with a screen play by Dudley Leslie, Marjorie Deans and Dennis Johnston, adapted from the play The Trouble by Dudley Sturrock and Noel Scott. This drama film, which tells the story of a British soldier and an Irish police officer who both fall in love with the sister of an IRA leader, was controversial at the time. The Brian Desmond Hurst website commented that 'Ourselves Alone was banned in Northern Ireland at the time of its release in 1936 although it has now achieved the recognition it deserved and is shown in museums and other public access points in Northern Ireland.' Wikipedia: Ourselves Alone Watch a clip on YouTube: Ourselves Alone In 1936, Terry Trench was once again an (uncredited) assistant cutter under James Corbett on the feature film The Tenth Man (1936) [68 mins], a British International Pictures film made at Elstree. This drama film, also directed by Brian Desmond Hurst, was based on the play by W Somerset Maugham about a businessman who believes that nine out of ten men are corrupt or weak. Wikipedia: The Tenth Man Wartime work for the Crown Film Unit, 1943-1945 In 1939, with the outbreak of the Second World War, the Crown Film Unit was created to make documentary films for the Ministry of Information. Terry Trench joined the Crown Film Unit, and worked on Close Quarters (1943) [75 mins] as an (uncredited) assistant sound cutter. This short film, issued in the USA as Undersea Raider, was produced by Ian Dalrymple, directed by Jack Lee, with photography by Jonah Jones and sound recording by Ken Cameron. It was intended to give an authentic impression of a wartime submarine patrol in the North Sea, with the submariners playing themselves on board their submarine HMS Tribune (renamed 'Tyrant' for the film). In a review on IMDb.com, 'earthtracer' comments that: 'This film gives an excellent idea of what it was like to fight one of His Majesty's submarines during World War II. It is probably the most authentic footage of its kind ...' Synopsis on BFI ScreenOnline: Close Quarters Watch the whole film on the Imperial War Museums website: Close Quarters Terry Trench worked as an (uncredited) sound cutter on The True Story of Lili Marlene (1944) [21 mins], directed and written by Humphrey Jennings. This propaganda film about the song Lili Marlene first shows the song inspiring German soldiers and then being adopted by the Eighth Army in North Africa. Like Close Quarters, it is a reconstruction that used non-actors to re-enact their experiences. Watch the whole film on Internet Archive: The True Story of Lili Marlene Two Fathers (1944) Terry Trench is credited as editor of Two Fathers [13 mins], which was directed by Anthony Asquith, produced by Arthur Elton, shot by cameraman Jonah Jones, with sound recorded by Ken Cameron. Based on a short story by VS Pritchett, the film tells of a conversation between an English father (played by Bernard Miles), whose son is the RAF, and a French father (played by Paul Bonifas), whose daughter is in the Resistance. Two Fathers is described by Tom Ryall in Anthony Asquith as 'a brief poignant tale with a mild hint of feminist sentiment'. Wikipedia: Two Fathers Photographs of cast on aveleyman.com: Two Fathers |

|

|

|

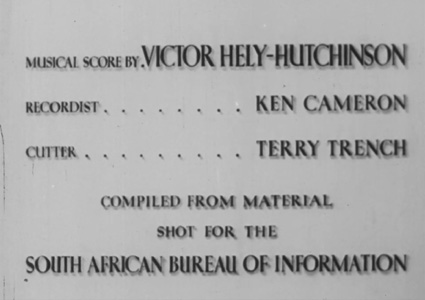

Know Your Commonwealth (1): South Africa (1944) Terry Trench worked on Know Your Commonwealth (1): South Africa [14 mins], in which he is one of three credits, as 'cutter'. The other two credits are for the composer, Victor Hely-Hutchinson, and the recordist, Ken Cameron. The film is billed as 'Compiled from material shot for the South African Bureau of Information'. The film describes the contribution of South Africa to the allied war effort. The commentary optimistically states that: 'In this common danger, we have also learnt something - learnt to live and work together. Blacks and whites, men and women, are working in our munition factories. Together, whatever our creed and whatever our race, we who want liberty for ourselves are making guns for the war and ploughshares for the peaceful cultivation of our country'. This was just five years before apartheid was introduced. Watch the whole film on YouTube: Know Your Commonwealth (1): South Africa |

|

|

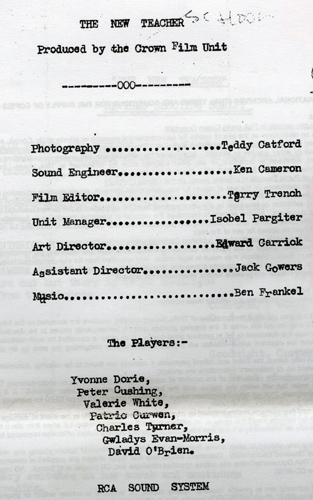

The New School (1944) The New School (working title The New Teacher), was directed by Rodney Ackland and edited by Terry Trench, with photography by Edwin Catford, music by Benjamin Frankel, and a cast that included Peter Cushing. This wartime film was made to encourage women to train as teachers, but appears to have received minimal distribution. According to the Bradford City of Film website: 'In 1944, playwright Rodney Ackland made a documentary in Ilkley called The New Teacher (aka The New School) for the Ministry of Information (MoI). The film featured Peter Cushing but, as the MoI considered it subversive, it was banned and became a 'lost' title in the Cushing filmography. To this day it has never been seen.' A slightly different account is given by the Yorkshire Post in a 2013 article about Peter Cushing: 'In a movie career lasting 47 years Cushing never set celluloid foot in Yorkshire save for one mysterious project that never saw the light of a projector. For two months in 1944 he worked with the playwright Rodney Ackland on a 20-minute documentary short entitled The New School. It was commissioned by the Ministry of Education, produced by the Crown Film Unit and shot on location in Ilkley. Ackland contrasted a cramped mid-Victorian council school with a modern, progressive counterpart. Finished and presented to its government masters it was promptly banned.' The New School was filmed, at least in part, at Homerton College, Cambridge, which has (in its archive) photographs and a script with a list of cast and crew on its front page. Homerton College Archive: The New School A copy of the film was finally tracked down by Homerton College's archivist, Svetlana Paterson, in 2021. Homerton College Archive: The search for the lost film A screening of The New School took place at the Arts Picturehouse, Cambridge, on 30th April 2022. The screening was followed by a discussion of the film and its historical and education context, chaired by Dr Peter Cunningham (historian and educationist at Homerton College), with contributions from Prof Peter Mandler (Professor of Modern Cultural History, University of Cambridge); Dr Sue Swaffield (University Senior Lecturer in the Faculty of Education); Ruchi Sabharwal (Director of Teaching and Learning at a community academy trust in Cambridgeshire); Steve Watts (Emeritus Fellow and Tutor in English, Homerton College); David Whitley (Fellow of Homerton College, who taught film, poetry and children's literature); and Nick Trench (artist and writer, son of the film's editor, Terry Trench). The context for the making of the film in 1944 was the Emergency Training Scheme for Teachers (1945-1951), which was set up to increase the recruitment of teachers and reduce the length of their training course to one year. This was necessitated by the 1944 Butler Education Act, which provided for free universal secondary education up to the age of fifteen, and so created the need for thousands more teachers. At the same time, the removal of a marriage bar in 1944 allowed women to continue teaching after marriage. |

|

|

|

This Was Japan (1945) Terry Trench was one of two editors (with Alan Osbiston) on This Was Japan [11 mins], directed by Basil Wright, with commentator Esmond Knight, music by Ben Frankel and sound recorded by Ken Cameron. The film depicts Japan's pre-war and wartime Cult of the Emperor and militaristic policies. As noted by Katherine Howells in her blog 'Depicting Japan in British propaganda of the Second World War' on The National Archives website, the film 'ended on a more positive note predicting the end of militarism in Japan's future', which she explains as due to a desire by The Ministry of Information 'to improve British attitudes to the future of Japan'. Watch the whole film on VPRO, a Dutch public broadcasting corporation: This Was Japan |

|

|

Post-war work for the Crown Film Unit, 1946-1952 In 1946, the Ministry of Information was abolished and replaced by the non-governmental Central Office of Information. The post-war films made by the Crown Film Unit often reflect the aftermath of war, social issues, and the relationship between Britain and its colonies. |

|

|

|

Jungle Mariners (1946) Terry Trench edited Jungle Mariners [15 mins], which was produced by Basil Wright and directed by Ralph Elton, with photography by Denny Densham, sound recording by Ken Cameron, and music by Elisabeth Lutyens. Jungle Mariners was Elisabeth Lutyens's first complete film score. This short film re-enacts the experience of Royal Marines patrolling in Burma, narrated by the officer in charge of the patrol. Synopsis on Colonial Film: Jungle Mariners Watch the whole film on YouTube: Jungle Mariners |

|

|

|

The Way from Germany (1946) The Way from Germany [11 mins] was edited by Terry Trench (and de facto director), produced by Basil Wright, with sound recording by Ken Cameron, music by Elisabeth Lutyens, and a commentary written by novelist Arthur Calder Marshall. The film is about the attempt to return eighteen million freed prisoners to their homes after the defeat of Germany; it shows slave labourers being liberated by the allies, and the establishment of camps for displaced persons. Synopsis on BFI ScreenOnline: The Way from Germany Watch the whole film on the Imperial War Museums website: The Way from Germany or on the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum website: The Way from Germany The Way from Germany is listed as one of the main films produced in 1946 in 'British Cinema and Society: Chronology 1939-1951' on Kinoeye (a University of Warwick blog). The film is also included in the BFI Education Guide to 'Refuge Britain?': 'Fleeing Home' A brief review in Monthly Film Bulletin in May 1947 commented that 'This film is well done, and would be excellent for Youth Club discussion groups, for UNO propaganda purposes, and, more generally, for reminding the more fortunate people of these islands of the sufferings of their Continental neigbours.' Partners (1946) Partners was edited by Terry Trench, with a commentary written and spoken by Dr Julian Huxley, photography by Robert Kingston Davies, music by John Greenwood, and sound recording by Ken Cameron. It was a short film about partnership between African and European people in the administration of East Africa, was made for the Colonial Office by the Crown Film Unit. The film was described as 'distinctly unsatisfactory' by the Education Panel Viewing Committee of Monthly Film Bulletin (January 1946). |

|

|

|

The Railwaymen (1946) and Along the Line (1947) Terry Trench was the (uncredited) editor of The Railwaymen [22 mins], which was directed by Richard Q McNaughton, with a script by novelist John Mortimer (all uncredited). This short film gave information about various careers on the railways, and was billed under the title as 'One of a film series about jobs'. Watch the whole film on YouTube: The Railwaymen A shorter version, Along the Line [15 mins] (with credits, including Terry Trench as associate editor) was also released. Watch the whole film on BFI Player: Along the Line Know Your Commonwealth (5): Southern Rhodesia (1946) Know Your Commonwealth (5): Southern Rhodesia was edited by Terry Trench, and produced by Basil Wright, with a commentary written by John Mortimer, music by John Greenwood, and sound recording by Ken Cameron. It is a short film about modern industry in Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). According to the BFI's Background Films Viewing Committee: 'This film ... only claims to give a bird's-eye view of its subject. It is, therefore, too fragmentary to be of much educational value ...' (Monthly Film Bulletin, May 1946) Tea from Nyasaland (1946) Tea from Nyasaland [9 mins] was produced by Basil Wright, photographed and edited by Robert Kingston Davies, with Terry Trench as supervising editor (all uncredited). It was made for the Colonial Office, and shows the cultivation of tea in Nyasaland (now Malawi). Synopsis on Colonial Film: Tea from Nyasaland According to the BFI's Geography Films Viewing Committee: it was 'a plain straightforward film', whose 'production is good' , and which is 'to be recommended for showing to such gatherings as school geography societies'. (Monthly Film Bulletin, November 1947) Home and School (1947) Home and School was directed by Gerard Bryant, shot by Jonah Jones, and edited by Terry Trench, with a script by John Mortimer, photography by Jonah Jones, and music by William Alwyn, whose annotated score is in the archive of the University of Cambridge. The film was intended to encourage parents to collaborate with schools in the education of their children. According to the BFI's Education Panel Viewing Committee: 'The treatment is pleasant though the film itself is a little "showy". It may be used for such audiences as Women's Institutes and Y.M.C.A.s.' (Monthly Film Bulletin, June 1948) Home and School was the start of a long working relationship between Terry Trench and the director and scriptwriter Gerard Bryant. |

|

|

|

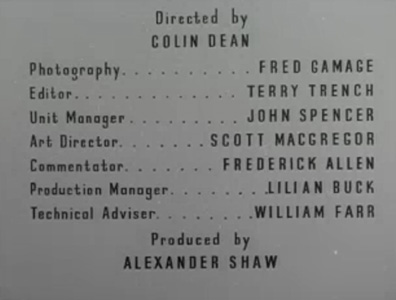

Shown by Request (1947) The Crown Film Unit's films were often shown by the Central Film Library's mobile film units, which travelled about the country setting up temporary cinemas in halls, canteens and schools. Their work is the subject of Shown by Request [18 mins], directed by Colin Dean, photographed by Fred Gamage, and edited by Terry Trench. A 2008 review by 'spuzz'on the Internet Archive website comments: 'Terribly odd film about how the movie got to where you are watching it from, fellow British Citizen! ... Noone looks like they're having a good time, which pretty much sums up 1950's Britain I guess.' A comment from 1948 is more charitable: 'This is an interesting film, which might well be screened to audiences ... so that they may appreciate the hard work which lies behind these programmes ...' (Background Films Viewing Committee, Monthly Film Bulletin, February 1948). Watch the whole film on Internet Archive: Shown by Request |

|

|

|

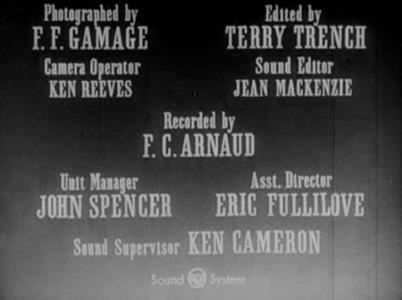

Voices of Malaya (1948) Voices of Malaya [35 mins] is credited as 'made by Ralph Elton & Terry Trench'. Elton headed the film unit in Malaya, which included cameraman Denny Densham, while Trench led the editorial team in London. It was scripted by VS Pritchett, with music by Elisabeth Lutyens. Watch the whole film on Colonial Film: Voices of Malaya An account of the content and process of making Voices of Malaya on the Imperial War Museums website notes that the film unit in Malaya under Ralph Elton shot 250,000 feet of film, which was 'then left to a team in Britain, headed by Terry Trench, to edit'. Cameraman Denny Densham wrote about the editing process (Colonial Cinema, June 1948): 'Voices of Malaya was really made by two distinct teams, the production unit of four who saw it through the camera in the East, and the assembly unit who put it together in the United Kingdom. It is perhaps strange to realise that the production members saw their rushes upon return, and then retired, as it were from the film. It was taken over by Terry Trench, who with his team started the gargantuan task of moulding a shape to the film. To Terry goes the credit for the idea of "Five voices", and to sound editor, Jean MacKenzie, for the construction of the admirable sound-effects tracks. Upon entering the cutting rooms during the early days of the assembly one became lost in a "jungle of tin cans." Many editors would have shied at the task of producing anything but factual travelogue from this mass of unlinked material.' The analysis of Voices of Malaya on the Colonial Film website remarks that: 'It was difficult to complete the film because of the rapidly changing political situation within Malaya. Ralph Elton noted in 1946 that "script writing was very difficult. We would anticipate history and find that next week we were hopelessly out of date" (The Straits Times, 4 August 1946, 4). Elton and his team (who became the nucleus of the Malayan Film Unit) started filming in 1945, but the film was finally released in 1948, by which time the political situation was completely different. Ian Aitken, in his 2016 book The British Official Film in South-East Asia argues that Voices of Malaya shows 'a "purposeful" project ... to reveal how the "voices of Malaya", those of the various races, have achieved a renewed sense of integrative commonality following the tragedies of war.' Aitken comments that 'no specific policy or propaganda ends are served here at all, and the key notions depicted relate to generalised issues of modernisation, communication, social improvement, equality and democracy'. He thus presents the film-makers as having an idealistic and optimistic view of the country's future. In his 2013 article 'Distant Voices of Malaya, Still Colonial Lives' (in the Journal of British Cinema and Television), Dr Tom Rice argues that 'Voices of Malaya illustrates the often-overlooked movement of British documentary film-makers, ideologies and practices into the colonies after the war. The Griersonian tradition - with its purported humanistic, liberal, pedagogical agenda - found a fresh outlet within the postwar colonies as part of the "nation-building" process.' Part of that pedagogical agenda was to help set up 'a local, instructional cinema' - the Malayan Film Unit. However, Rice argues, 'this emerging local cinema was increasingly shaped by a form of politically conservative, instructional cinema ... at odds with Griersonian traditions.' Voices of Malaya, Rice states, 'was caught in the midst of local and international political shifts and provides an eloquent testimony to this transitional moment in both colonial and documentary cinema.' The editing of the film in London meant that the shape and message of the film was determined (however benignly) by non-Malayans - primarily by Trench. Rice comments that, while film equipment was increasingly placed 'in the hands of the "colonised"', 'post-production work continued to be carried out in London'. For Voices of Malaya, the footage shot by Ralph Elton 'was sent back to England where editor Terry Trench was tasked with creating a film ...'. Rice writes that 'it was Trench who ultimately manufactured the narrative structure of the film, introducing the five voices. This structure, closely aligned to prewar documentary cinema from Song of Ceylon (1934) to Five Faces, reinforces the film's documentary aesthetic.' Dr Nadine Chan in the abstract for her 2016 paper 'A Time-Lagged Medium: Colonial Documentary in British Malaya and the Asynchronous Reproducibility of Reality', in which she discusses Voices of Malaya, comments that while 'the workings of colonialism's visual cultures were very much dependent on the quick and easy reproducibility of images through the technologies of the cinema - films that cultivated 'a sense of familial intimacy and immediacy that sought to foster ideas of imperial modernity and Commonwealth camaraderie', ... 'film proved to be an unexpectedly time-lagged medium' because 'inequalities in technological access meant that post-production services were still carried out in London.' Dr Chan draws attention to what she calls 'colonial time': 'anachronistic zones where ... the inequalities of technological availability meant that the reproducibility of the image was not instant, but stretched out the geographical space between colony and metropole.' A comment from 1948 reveals how much less problematic Voices of Malaya was regarded at the time, at least in the UK: 'The film leaves [the people of Malaya] still struggling with the enormous task [of post-war reconstruction]; it leaves one dissatisfied, but there can be no cut-and-dried finale for such a sincere and intelligent record.' (Monthly Film Bulletin, May 1948) A Yank Comes Back (1949) A Yank Comes Back [42 mins] is a story film, starring Burgess Meredith, directed by Colin Dean, edited by Terry Trench, photographed by Edwin Catford, and with music by Spike Hughes. An American GI returns to post-war Britain. Synopsis on All Movie: A Yank Comes Back According to a 1949 New York Times review entitled 'An Optimistic British Documentary', 'Mr. Meredith represents a GI who is curious to discover how Britain is getting along since the Americans went home. He finds that the British are doing marvelously well.' ... 'By all odds the British lion should have been down for the count, Mr. Meredith says. That he is up and stirring about is due cause for cheering.' However, the reviewer remarks that the film is 'not in a class with the many remarkable documentaries which came out of England in her greatest hours of stress.' A contemporary British review comments: 'The film is disjointed, and tries too hard to be informal, but there is no doubt about its sincerity and general air of goodwill.' (Monthly Film Bulletin, February 1949) |

|

|

|

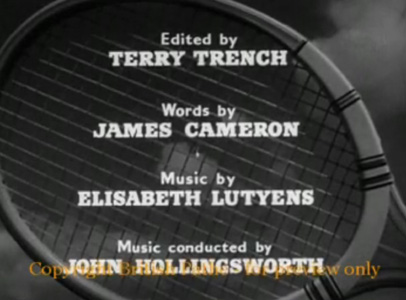

Daybreak in Udi (1949) Daybreak in Udi [40 mins] was directed by Terry Bishop, produced by John Taylor and edited by Terry Trench. It won the 1949 Oscar and BAFTA for best documentary for its re-enactment of the building of a maternity hospital in eastern Nigeria, in which the District Officer plays himself, Igbo villagers play the villagers, and a small number of actors take other roles. Wikipedia: Daybreak in Udi Watch the whole film on Colonial Film: Daybreak in Udi This is another film that is the site of post-colonial debate. The film is described by Patrick Russell (in his paragraph on director Terry Bishop in 'Five forgotten filmmakers' on the BFI website) as 'absorbing but uncomfortable'; Russell comments that its 'interpretation of colonialism hits several unintentionally disturbing notes'. Jo Pugh describes the film as 'uncomfortable watching for a modern British audience' and 'a mildly unpleasant imperialist relic' in her 2013 blog 'Daybreak in Udi and the lost Oscar' on the National Archives website. And the BFI article on the Crown Film Unit comments that: 'This skilful drama-documentary's representation of Nigeria would now be considered deeply politically incorrect (though director Terry Bishop and producer Max Anderson were two of the most committed left-wingers in the film industry).' A substantial analysis of Daybreak in Udi can be read in Ben Page's 2014 article 'And the Oscar Goes to ... Daybreak in Udi': Understanding Late Colonial Community Development and its Legacy through Film'. In his abstract, he comments that: 'The film also discloses a late colonial 'socio-geographical imaginary', articulated through a hierarchy of specific social categories (administrative officers, teachers, peasants, elders, women and troublemakers), spatial locations (urban, rural) and the distinctions between them (modern/reactionary, leader/worker, audible/silent).' In addition, the article discusses the 'ongoing paradoxes of "self-help development", namely that it usually requires an outsider'. Nwachukwu Frank Ukadike in Black African Cinema (1989) argues that in Daybreak in Udi and other films 'African characters are never developed or given a chance to express their feelings but are structured to further the fabricated notion that Africa needs British help to control its own affairs'. He further comments that Daybreak in Udi was 'berated by the nationalist press [at the time] as "yet another film unit come out to our country to depict us as naked savages and unfit to rule ourselves"'. There is a story that Chinua Achebe was motivated to write his classic novel Things Fall Apart by the film. Ben Page [2014] writes: 'Writing in the Nigerian newspaper The Sun, Austine Amanze Akpuda argues that the Egwugwu story in Chinua Achebe's classic novel Things Fall Apart (1958) was probably influenced by seeing or, at the very least, hearing about Daybreak in Udi, which was shown in Umuahia in 1949.' The film can be see more positively as a record of Igbo culture in the late 1940s. Ynaija.com (a Nigerian media and culture website) notes in a 2020 Media Blog that Daybreak in Udi was 'the first Nigerian language [Igbo] film to win an Oscar', and comments that the conflict between tradition and 'progress' are still relevant today. The blog also reflects on the fact that 'The film is also a rare (if somewhat staged) look into what Igbo culture must have looked like as it transitioned from purist to diluted by Western influence and the kind of resistance Igbo people put up against cultural invasion.' However, the writer also draws attention to the problem of the 'benevolent' West and the question of where power still lies: 'There is also the fact that Daybreak in Udi ... was ... shot and produced by white filmmakers', ... a 'trend that continues to this day where only white storytellers have sufficient funding to tell indigenous stories'. Daybreak in Udi is mentioned by Dr David Pratten in his 2018 article 'Understanding the Niger Delta's agaba masquerade tradition', where he discusses how 'In colonial propaganda films, like the Oscar-winning Daybreak in Udi (1949), the forces of tradition, male gerontocracy and conservatism were represented by agaba masqueraders.' He reveals how these masquerades can also be perceived by Nigerians as 'something of the past, of traditional belief systems, and by Christians ... as demonic', and asks why young Nigerian men continue the tradition; one of his conclusions is that 'agaba presents a powerful critique of the Nigerian social fabric. It is a space in which young men expose the inequalities and iniquities of their position from the margin, projecting advantage onto their own disadvantage.' In Dr Femi Okiremuete Shaka's 1994 thesis 'Colonial and Post-Colonial African Cinema (A Theoretical and Critical Analysis of Discursive Practices)', it is argued that in Daybreak in Udi 'the main African characters (the only European character being Chadwick, the District Commissioner) are not the caricatured stereotypes of Africans that one finds in colonialist African cinema. Rather, representation in this film adheres to the tradition of social documentary in which villagers are seen engaged in mass literacy campaigns and self-help community development' and that 'traditional rulers are represented as partners and people capable of social progress'. Dr Shaka makes the point that this film highlights the theme of self-development, and quotes from the opening sequence of the film: 'the Abaja Ibos, have undertaken an ambitious programme of community development which has seldom been equalled. Together they are teaching themselves to read and write, and are building schools, maternity homes, cooperative shops, and many miles of roads.' Dr Shaka also points out that the move to build a maternity hospital comes initially from the villagers themselves, that the scene of public debate is authentic, and that the relationship between the District Officer and the villagers is one of respect for their culture. 'Furthermore, throughout the film, he [Chadwick] insists that the good cultural practices of the people should not be tampered with in the quest for development.' The thesis distinguishes Daybreak in Udi from 'traditions of colonialist African cinema which represents Africans as degenerate barbaric people'. Having said that, Dr Shaka also points out that encouraging community self-development projects was also a money-saving exercise for the colonial rulers - 'one that has been passed on to post-colonial governments in Africa where the system has become one of the abused loop-holes for siphoning public funds into the private accounts of government officials.' In my opinion, there are two main ways in which present-day viewers may well find Daybreak in Udi uncomfortable. The first, and most obvious, is the sheer fact of colonial power: there is a huge unarticulated disparity of power between the Igbo villagers and the Distict Officer, Chadwick, who is the representative of British rule, however benign and respectful Chadwick is of traditional Igbo culture. The benignity and respect in the context of this enormous inequality has, in fact, a tendency to suggest the opposite: that in different circumstances the power could be used in ways that are neither benign nor respectful. This film is after all a propaganda film, intended to persuade people round the world and in Nigeria itself of the benefits and the light-handedness of British rule, and as such is essentially dishonest. Demands for independence were already being made in Nigeria before this film was made. Nigeria became the autonomous Federation of Nigeria in 1954, only five years after this film was released, and Britain agreed in 1958 that Nigeria would gain independence in 1960. Daybreak in Udi as British colonial propaganda is discussed in some depth by Louise F. Müller & Meera Venkatachalam in their 2022 article 'The notions and imagination of space and time in British colonial and African intercultural philosophical cinema'. They comment that the film creates (or reflects) a hierarchy with Chadwick at the top, the African évolués in the middle and the Igbo villagers at the bottom, noting that the évolués wear western clothing and are named characters, unlike the Igbo villagers. I believe that the second area of discomfort for contemporary viewers concerns the format of the film itself. It is presented as an accurate retelling of a true story in which the people involved re-enact their own actions and speak their own words. However, Daybreak in Udi is clearly a hybrid; while Chadwick and the villagers play themselves, the two teachers who act as go-betweens, the main objector to the plans ('Eze'), and the midwife are all are played by actors (Fanny Elumeze, Harford Anerobi, Josef Amalu and Joyce MgBaronye). As a result, we are left in a state of uncertainty as to how much the story is truly authentic and how much it has been altered to make it more dramatic as a story or more effective as propaganda. By presenting the film as a documentary, including entering it into the documentary category for the Oscars, the film was given a kind of truth value, an authenticity, which now seems dubious. Didi Cheeka in her 2023 article 'A New Period in History: Decolonizing Film Archives in a Time of Pandemic Capitalism' describes Daybreak in Udi as 'a fictional film presented as documentary', an example of how 'how the imperial camera's access to colonized human raw material could produce a regime of truth for scholars, curators, artists, and researchers to consult as benign sites of knowledge'. This re-enactment format using the real people that were involved in the original event was popular in documentary film-making at the time; it was seen as democratic, allowing people to have a voice who didn't usually have access to the means of voicing their concerns and opinions or of depicting their lives in an authentic way. Other Crown Film Unit films that used a similar approach include Jungle Mariners (1946) - see above. However, this approach, while clearly well-intentioned, can create a rather stilted effect, making a film seem less convincing than true fiction played by actors, or purely fact-based documentary, or 'instructional' films, such as were made by the Colonial Film Unit. In this context, it is noteworthy that Daybreak in Udi was made by the Crown Film Unit rather than the Colonial Film Unit; Dr Tom Rice comments (in his 2013 article 'Distant Voices of Malaya, Still Colonial Lives') that the 'differing ideologies and formal approaches taken by Crown and the Colonial Film Unit are perhaps most neatly illustrated through those subjects that were filmed by both units. A notable example here is ... Daybreak in Udi, Terry Bishop's 40-minute film of community development in Eastern Nigeria. The same subject was addressed by the Colonial Film Unit in a series of short, instructional films made for local audiences in East Africa in 1948 and 1949.' So are there any reasons to watch Daybreak in Udi, now nearly 75 years old? It is clearly interesting as an example of colonial propaganda, made towards the end of colonial rule in Nigeria and presenting that rule in a benign light. It is also interesting as an example of the mid-twentieth century fashion for re-enactment in documentary film-making. In the end, however, its main interest lies in capturing a moment in time - being a partial record of both traditional Igbo culture and British colonial culture in the late 1940s. A minor footnote to Daybreak in Udi is that the Oscar statuette itself went missing, a story retold by Jo Pugh in 'Daybreak in Udi and the lost Oscar' in a February 2013 blog on the National Archives website. It seems that the sound recordist Ken Cameron kidnapped the statuette as a protest against the Crown Film Unit being closed down. He was persuaded to return it once it had been confirmed that the Oscar had been awarded to the 'British Information Services' and so belonged to the government. The statuette was borrowed in 1952 by the Foreign Office for display at the headquarters of British Information Services in New York, and has never been seen since. Trooping the Colour (1950) Terry Trench and Terry Bishop worked again together on Trooping the Colour 1949 [36 mins], made by the Crown Film Unit for the Foreign Office. 'This dignified, dramatic and highly colourful ceremony is superb material, and the film has been extremely well done. ... Military music and colour combine to make an exciting picture.' (Monthly Film Bulletin, April-May 1950) El Dorado (1951) El Dorado, a documentary about British Guiana, was directed by John Alderson and edited by Terry Trench, with a commentary written by James Cameron and music by Elisabeth Lutyens. Monthly Film Bulletin (May 1952) commented that El Dorado was one 'of the best recent documentaries', and that the 'material has been effectively edited by Terry Trench'. El Dorado was shown at the 1952 Cannes Film Festival in the Short Films competition. Synopsis on Colonial Film: El Dorado Basil Wright described El Dorado in Sight and Sound in 1952 as 'beautifully edited by Terry Trench, and with a superb score by Elisabeth Lutyens'. He also noted that the film was not sponsored: John Alderson (director) and Reg Hughes (camera) 'rustled up enough production funds (through independent film-financing ...), and plunged into British Guiana, living rough and shooting like mad all the time.' |

|

|

|

Out of True (1951) Out of True [41 mins] is a drama-documentary, starring Jane Hylton, directed by Philip Leacock, with editor Terry Trench, lighting cameraman Jonah Jones, sound supervisor Ken Cameron, art director Scott MacGregor, music by Elisabeth Lutyens, and a screenplay by Montague Slater. The film is intended to show a sympathetic approach to the subject of clinical depression. Wikipedia: Out of True Watch the whole film on BFI Player: Out of True Philip Leacock, in an interview in 1987 with Stephen Peet, explained that 'a movie called Snake Pit had been released shortly before, which made mental hospitals ... really very horrifying. And it was felt that this not true in British mental hospitals, so we did a quite serious story ... trying to say that you go into a hospital and they try and cure you and help you and so on, and it's not a 'snake pit' situation.' Monthly Film Bulletin (June 1951) commented at the time that '... though its intentions are genuine, and its application is conscientious, Out of True is hardly likely to break down popular prejudices any more than The Snake Pit did.' BFI Player comments on Out of True that: 'Its mix of true and false notes is what makes the film's efforts to destigmatise so fascinating. In the script, insightful intentions vie with snatches of caricature and sexism; in the production, over-stylised sensationalism risks overwhelming sensitive moments.' |

|

|

|

Royal Scotland (1952) Terry Trench's last film for the Crown Film Unit was Royal Scotland [10 mins], a short documentary about royal connections with Scotland, which also received an Oscar nomination, and was the last film made by the Crown Film Unit at Beaconsfield. It was directed by Gerard Bryant and shot by Jonah Jones. Gerard Bryant recalled: 'There was no script, and all I did was to provide Terry with a number of sequences which ... he merged into a very attractive ten minutes.' Watch the whole film on YouTube: Royal Scotland The Crown Film Unit Between 1939 and 1952, the Crown Film Unit made about 130 films. Many of these films are docu-dramas or 'story documentaries', in which people's stories were (partially) scripted and shaped, although they often play themselves. The Crown Film Unit closed in 1952. Denis Forman writing in Sight and Sound in 1952 on the closure of the Crown Film Unit commented that: 'It would be sad indeed if documentary were to lose the genial and understanding leadership of Ralph Nunn May, Margaret Thomson's precious talent in the handling of children and young people, the enthusiasm and instructional skill of Richard Warren, Ken Cameron's unique experience as sound director and Terry Trench's authority in the cutting room.' Mid 20th-century documentary films and their funding Until the mid-1950s, most of the films that Terry Trench worked on were intended for education, propaganda or entertainment, and they were predominantly funded by the state. The government funded the Crown Film Unit and other government film units, such as British Transport Films and the National Coal Board Film Unit, and also sponsored films from independent film units. Some commercial companies had their own in-house film units - most notably Shell, who set up their own film unit under Edgar Anstey in 1934 - but most companies commissioned films from independent producers when they wanted them. Documentary film-making requires money, but it does not make money directly through sales. The sponsors, whether commercial companies or government departments, have an agenda and a view of what they want the film to achieve. However, the film makers themselves are both technicians and artists, who have a vision for a film. It is the job of the producer to balance the vision of the film makers against the agenda of the sponsor. In the case of publicly-funded films, a concept of public service often dominated, which allowed the artists and technicians a good deal of autonomy. Even in the private sector, films were not always directly promotional. Arthur Elton, who succeeded Edgar Anstey as the Shell Film Unit's main producer, argued that the benefit to a sponsor was in inverse proportion to the number of times that a sponsor's name appeared in a film, and convinced Shell to sponsor many films (such as the Craftsmen series) that make only the most oblique reference to Shell's commercial interests. Freelance work for many production companies in the 1950s and early 1960s Throughout the rest of the 1950s and the early 1960s, Terry Trench worked for many different production companies and film units, including three films for the Pathé Film Unit, two for the National Coal Board Film Unit, and two for British Transport Films. He became a producer for Produzione Santa Monica Film Unit in Rome in 1953-4, and a director for the Syracuse Film Unit in Athens in 1955-6. From 1957 to 1959, Terry Trench lived in Australia, and worked as an advisory editor for the Shell Film Unit of Australia. |

|

|

|

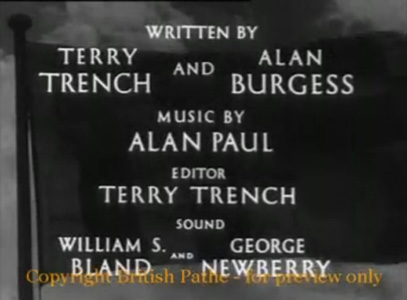

Prince Philip (1953) The British Pathé film Prince Philip [18 mins] was co-written (with Alan Burgess) and edited by Terry Trench, and directed by Howard Thomas (1909-1986). Watch the whole film on British Pathé: Prince Philip |

|

|

|

Elizabeth is Queen (1953) Trench worked with Howard Thomas for British Pathé as one of three editors, with Lionel Hoare and A. Milner-Gardner, on Elizabeth is Queen [51 mins]. The commentary was written by the poet John Pudney, and the director of photography was Terry Ashwood. The film is a Technicolor record of the coronation. Watch the film in sections on British Pathé: Elizabeth is Queen |

|

|

|

The Way to Wimbledon (1954) Another British Pathé film was The Way to Wimbledon, which was directed by Franklin Gollings, edited by Terry Trench, with music by Elisabeth Lutyens and a commmentary read by the actor John Mills. It is a documentary about preparations for the Wimbledon tennis tournament. 'A certain freshness, in fact, is the keynote of this agreeable documentary. It is modestly and cleanly made, it responds to the atmosphere of its subject and inclines naturally towards the personal rather than the official - a welcome change.' (Monthly Film Bulletin, January 1953) Watch the film in sections on British Pathé: The Way to Wimbledon |

|

|

|

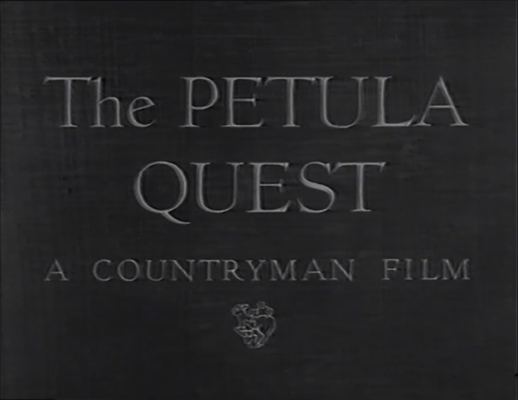

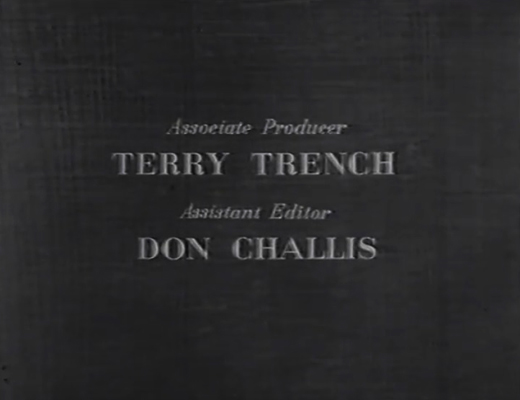

The Petula Quest (1955) Trench was associate producer (and editor) for The Petula Quest [14 mins], which was produced by Leon Clore and Grahame Tharp for Countryman Films. Don Challis was assistant editor, and the music was by De Wolfe. The film is about three scientists - Frank Evans (British), Dick Dickson (New Zealander) and Roland Sharmer (Malayan) - who drifted across the Atlantic on the North Equatorial Current from Dakar (Senegal) to the Barbados in a small boat (the Petula) in order to study the sea without disturbing it with engine noise and vibrations. They shot the footage themselves, and two of the scientists - Evans and Dickson - speak the commentary. The film was issued as part of 'The World of Life Series: A Journal of the Outdoors'. 'The film gives some idea of the effort involved, the conditions of living, but suffers from the fact that at the most interesting moments all three were inevitably occupied with doing something other than taking pictures. So the record, though sympathetic, is fairly sketchy.' (Monthly Film Bulletin, January 1956). Watch the whole film on YouTube: The Petula Quest The Gentle Corsican (1956) The Gentle Corsican, made by Harlequin Productions, was directed by Anthony Simmons, edited by Terry Trench, photographed by Walter Lassally, and narrated by Nigel Stock. It is a story film about a Corsican fisherman, who 'fears that his ten-year old son Nico may become so fascinated by the bikini-clad tourists with their underwater fishing equipment that he will lose his taste for their life on the rocks of Corsica' (Monthly Film Bulletin, June 1956), which describes the film as 'restful and affectionate', but comments that the story is told 'through a narrative commentary rather than visually.' The BFI entry for Anthony Simmons describes the film as 'strong on ambience, though anchored to a more conventional (and more heavily fictionalised) exotic travelogue'. Journey from the East (1956) This film was made by Jack Howells Productions for British Petroleum; it was directed by George Sturt, edited by Terry Trench, and filmed by Cyril Arapoff, a cinematographer and fine art photographer. It is a promotional documentary about an oil tanker, an oilman's son's birthday, and oil products from the Isle of Grain.Adventure On (1956) Adventure On [62 mins], a film directed by Thomas Stobart for the Film Producers Guild and sponsored by the agricultural machinery company Massey-Harris-Ferguson, was edited by Terry Trench, with music by Brian Easedale. 'Tom Stobart (who photographed The Conquest of Everest) covered twenty-seven countries and is seen interviewing numerous notabilities' in a film which demonstrates the 'increases in production made possible by mechanisation'. 'Stobart's agreeable personality, some excellent colour and the wide range of subject matter ... maintain the interest throughout', but the film is criticised for having an 'incessant, over-dramatised musical score'. (Monthly Film Bulletin, January 1957). By contrast, the BFI entry for Adventure On says that the musical score is 'a perfect complement to the photography of Tom Stobart's scenic worldwide landscapes'. The photograph below shows Terry Trench with Tom Stobart in the cutting room at Merton Park Studios, working on Adventure On. |

|

|

Native Dances of Papua and New Guinea (1957) One film that Terry Trench edited in Australia was Native Dances of Papua and New Guinea. This Land Australia (1958) While he was in Australia, Trench also directed This Land Australia [23 mins] for the Commonwealth Film Unit; this film, a 20-minute survey of the country, was produced by Stanley Hawes and Eric Thompson with Malcolm Otton and Richard Mason as associate directors. Summary and clips in Film Australia Collection: This Land Australia. Trench was also an adviser on a number of other films made by the unit. Invitation to Monte Carlo (1958) Back in England, Trench edited Invitation to Monte Carlo, released in the USA in 1961 as Love in Monaco, which was directed by Euan Lloyd for Richmond Film Productions. This is a Technicolor piece about a six-year-old orphan girl who takes a kitten as a present to the daughter of Princess Grace (Grace Kelly) and Prince Rainier of Monaco. It features Grace Kelly as herself, and Frank Sinatra. The Monthly Film Bulletin (September 1959) says that the 'treatment is professional but undemanding', and that 'the film has some sure-fire box-office ingredients - child appeal, kitten appeal, underwater shots of Prince Rainier as a diver ...' (the last of which were filmed by underwater cameraman, Egil S Woxholt). National Coal Board Film Unit The nationalisation of Britain's coal mines in 1946 created the National Coal Board, which commissioned films from both the Crown Film Unit and independent producers. In 1952, the NCB set up its own in-house film unit, the National Coal Board Film Unit, which made films until 1984. How to Instruct (1958) and The New Instructor (1959) Terry Trench edited two films for the NCB Film Unit, both directed by Ralph Elton: How to Instruct and The New Instructor, in which an experienced miner learns how to train new recruits. Kitty Marshall, an editor and producer at the National Coal Board Film Unit, was interviewed in 1988 by Gloria Sachs and Alan Lawson, and commented that: 'Terry was a lovely person and very good in ACT too, he was a very good ACT person ... I think he overdid the importance of the editor, but that's, you know, a matter of opinion and he was very, very, very keen and enthusiastic on his work, extremely good'. British Transport Films British Transport Films was started in 1949, with Edgar Anstey as Producer-in-Charge. BTF's films were intended to encourage rail travel and tourism. They rarely advertised rail or bus travel overtly, but encouraged travelling within Britain. Paul Smith reports that John Legard, one-time Chief Editor at British Transport Films, explained that it was the normal practice at BTF to have a small group of permanent employees, and for other staff to be brought in on temporary and freelance terms for particular projects, via the Association of Cinematograph, Television and Allied Technicians (ACTT) to 'keep productions fresh'. |

|

|

|

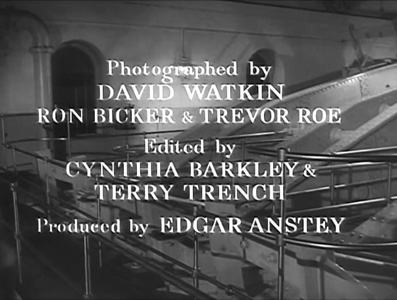

Under the River (1959) Terry Trench edited two films for British Transport Films, both produced by Edgar Anstey. The first was Under the River [27 mins], co-edited with Cynthia Barkley, about the construction of the Severn tunnel and the Cornish beam engines that keep it pumped dry, directed by RK Neilson Baxter. |

|

|

|

Three is Company (1959) Terry Trench's second film for BTF was Three is Company [30 mins], which shows three American tourists visiting Britain. It was directed by Tony Thompson and edited by Terry Trench, with music by Elisabeth Lutyens. Three is Company won Best Publicity Film in Rome in 1960 and a Diploma of Merit in Melbourne in 1964. Background to Performance (1960) In 1960, Terry Trench edited a Shell Film Unit production in Britain: Background to Performance, a documentary about Shell's research into fuels and lubricants, directed by Peter De Normanville. |

|

|

|

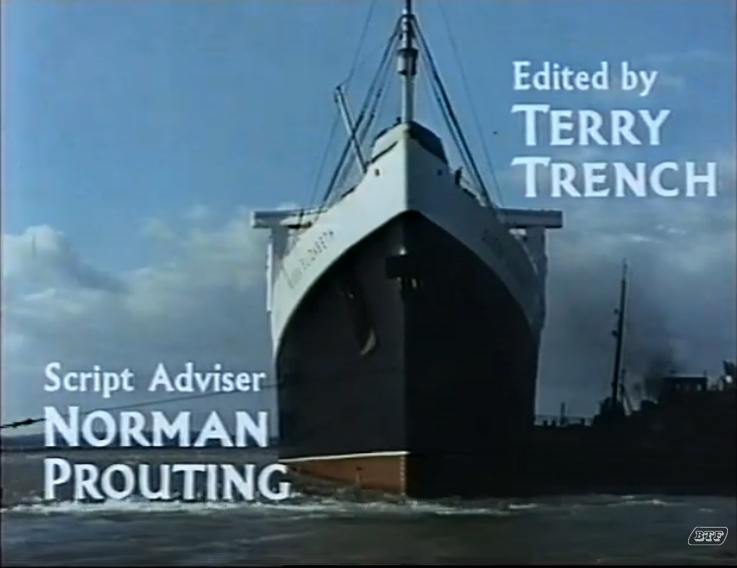

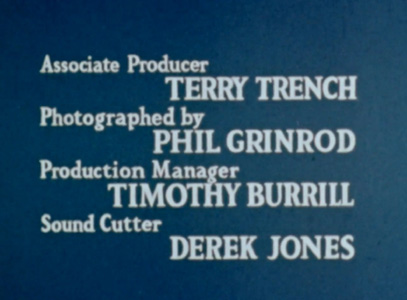

Hospital Team in Action (1960) Hospital Team in Action [16 mins] was a Samaritan Films production, written and directed by Michael Luke, with Terry Trench as associate producer, photographed by Phil Grindrod, spoken by Donald Houston, and produced by Anne Balfour-Fraser. It narrates the story of a young boy's illness with osteomyelitis, which leads to an explanation of various hospital careers, including nurse, radiographer, pharmacist, occupational therapist, and almoner. John Langley (uncredited) played the young boy. Watch the whole film on BFI Player: Hospital Team in Action The Skiers of Norway (1960) Terry Trench edited The Skiers of Norway (working title Song of Norway), directed and filmed by the British-Norwegian underwater cameraman Egil S Woxholt, who also wrote the music and lyrics. Woxholt had previously worked with Trench on Invitation to Monte Carlo. The Skiers of Norway was produced by Ewan Lloyd for Kingston Film Productions. The BFI entry for the film describes it as: 'A ski-ing musical! An introduction to ski-ing by way of song.' |

|

|

|

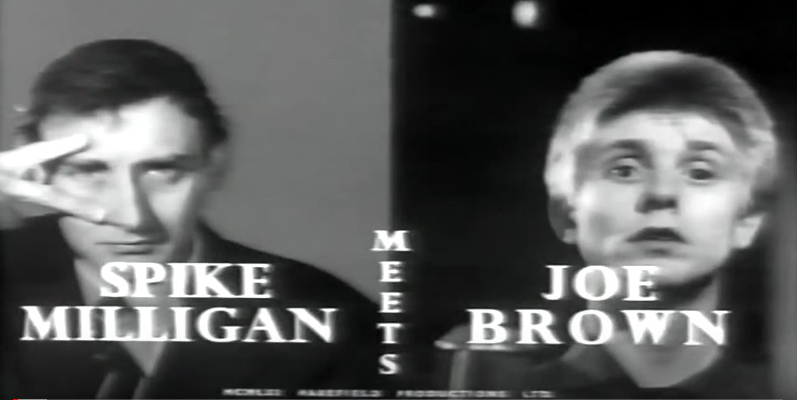

Milligan at Large (1961) Trench was reunited with Gerard Bryant for two comedies written and narrated by Spike Milligan. Milligan at Large: Spike Milligan meets Joe Brown [23 mins] takes a Goon-ish approach to pop music, with appropriate sound effects and visual gags. Described by Monthly Film Bulletin (November 1961) as a 'most promising start to a comedy series', the rock 'n' roll star Joe Brown's career is 'interpreted, reviewed, explained, analysed and commentated by Spike Milligan' in a running commentary that is 'an ironic, acid, satirical burlesque'. It was followed by Milligan at Large: Spike Milligan on Treasure Island WC2 [24 mins]. Both films were produced for British Lion by the Boulting Brothers. |

|

|

|

Bungala Boys (1961) Terry Trench returned to Australia and worked as associate producer and editor on Bungala Boys [58 mins], directed by Jim Jeffrey, a short children's feature film telling the story of boys setting up a life-saving club on the beach at Bungala, based on a childrens' book, The New Surf Club by Claire Meillon. The film won the Children's Film Award at Venice in 1962. Watch the first nine minutes of the film on YouTube: Bungala Boys. |

|

|

|

Bungala Boys was made by the Children's Film Foundation (CFF), a not-for-profit organisation that made films for children between 1951 and the mid-1980s, subsidised by the Eady Levy (a tax on box office receipts to support the UK film industry) for much of that time. 'Handsomely filmed on location in Australia, this is a sturdy if conventional tale of endeavour and its just reward, well up to CFF standards.' (Monthly Film Bulletin, January 1962) In his entertaining 2010 review of Bungala Boys on IMDb, 'travis_iii' comments that: 'Between 1971 and 1975, on any given rain-sodden Friday afternoon (and there were many of them), when it seemed just too cruel to send a herd of under 12s outside to chase a lace-up football around a field, the teacher taking games would announce to us, "OK kids, you're staying in and watching The Bungala Boys." I must have watched it a dozen times, but the thrill of seeing it never seemed to pale. There we were on a grey, wet winters afternoon in London staring at what seemed to be a sun-soaked slice of paradise.' He adds that: 'For years I thought that the Bungala Boys had to be a famous piece of Australian cinema, but in adulthood every Australian I met looked perplexed when I mentioned it.' Article with photographs from The Australian Women's Weekly of Wednesday 28 June 1961: 'Young stars shine in surf club film'. See also Oz Movies: Bungala Boys and WikiVisually: Bungala Boys New Look at London (1963) Trench directed and edited New Look at London, an 8-minute colour documentary about London, filmed by cameraman Mark McDonald entirely from a helicopter flying along the Thames, and with commentator Geoffrey Sumner. This film was produced by British Movietonews, to be shown in cinemas as a newsreel, and sponsored by the Commonwealth Relations Office and the Central Office of Information. The Inheritance (1963) Terry Trench edited The Inheritance, directed by Euan Lloyd and made by Highway Productions. This is a 'featurette' about a visit to Berlin by two actors, Albert Finney and Elke Sommer, who were two of the stars in The Victors, a feature film of 1963. The Victors, directed by Carl Foreman, follows a group of American soldiers through Europe during World War II, ending up in Berlin; Albert Finney appears as a Russian soldier and Elke Sommer as 'Helga'. The poster for The Victors claimed: 'The six most exciting women in the world ... in the most explosive entertainment ever made!'. |

|

|

|

Wonderful Norway (1964) Trench edited a second film directed by Egil S Woxholt: a travelogue called Wonderful Norway, made by Norseman Films Woxholt later worked on many feature films as an underwater and aerial photographer, including the James Bond movie On Her Majesty's Secret Service (1969). Watch a clip of Wonderful Norway on YouTube. The Mad Twenties (1965) Trench acted as an adviser on The Mad Twenties, an English adaptation by Leslie Mallory of a French documentary about the 1920s, Les Années Folles. This film was screened at the Theodore Huff Memorial Film Society at New York University on 16th November 1970. William K Everson, Professor of Cinema Studies, argues in the programme notes that the film 'makes a welcome change from the American approach to this kind of material. ... a non-hard-sell approach ... even the familiar is handled in a fresh manner ...'. Redonda In the 1960s, Terry Trench was made a duke of Redonda by his friend the poet John Gawsworth, King Juan I of Redonda, along with many others so honoured. Wikipedia: Kingdom of Redonda Derek Stewart Productions, 1963-1974 Between 1952 and 1963, Terry Trench's work had been insecure but varied: a mixture of corporate-funded and state-funded work, in Britain and abroad, documentary and fiction, as director and as editor. In 1963, Trench joined Derek Stewart Productions, and he worked there until shortly before his death. For the films mentioned below, Trench acted as primarily as executive producer (credited, as was normal in the documentary industry at the time, as 'associate producer') and/or editor, and occasionally as director or scriptwriter. The role of Executive Producer In Terry Trench's 1963 article 'Documentary in the Doldrums' in the Film & Television Technician, he explained his conception of the role of executive producer. He wrote that: 'Until recently, a high proportion of the good documentaries have come from a remarkably small number of units. This is due to the importance of the Executive Producer, because without good leadership, much of the skills of the writer, director, cameraman, editor, musician and sound recordist can be blunted in the film's final result.' Trench commented that, while sponsorship 'has been criticised for stifling the creativeness of film makers', 'this argument is refuted by the work of the ... Crown Film Unit, all of which was Government sponsored.' Trench believed that it was the job of the executive producer to give 'specialist advice' to the sponsor (and indeed that it was that advice that an executive producer was paid for) and to fight for their film; otherwise, they not only risked the unit's chances with the sponsor's next project, but also the creation of 'a dull film made by a bored unit'. He argued that it was the job of the 'sensitive creative producer' to analyse a proposed subject and suggest 'an effective film style in interpretation'. The executive producer should even be 'able to tell the sponsor when a proposed subject is unsuitable for filming, and, with a reputation for honesty and judgment, is in turn asked by the sponsor to suggest subjects.' Gerard Bryant recalled that Terry Trench: 'hated any hint of advertising to creep into his films, and he would never pander to sponsors. He maintained that in the long run the sponsors would thank him - and many of them did.' Derek Stewart Productions sponsors Derek Stewart Productions mainly made films for corporate sponsors, and one of the biggest sponsors was British Petroleum. BP Video Library: 'A history of film in BP' Terry Trench worked on about nineteen films sponsored by British Petroleum, many of which are documentaries aimed at marketing a product or training a workforce. On the other hand, a series of films sponsored by BP about hovercraft (then a new invention) was aimed at a general audience. Other films for Derek Stewart Productions that Terry Trench worked on were sponsored by different companies and organisations with an interest in that area. For example, a number of documentaries for doctors and medical students were sponsored by pharmaceutical or other related companies, including Smith and Nephew, the British Oxygen Company, Merck Sharp and Dohme, and Geigy. Some films about building and development were sponsored by the National Federation of Building Trades Employers (NFBTE), Bovis, and Arup. What to Eat (1963) What to Eat, a documentary for domestic science teachers about nutrition, was sponsored by Bovril. It was directed by Gerard Bryant, with associate producer Terry Trench, photographed by Harold Case, edited by Julian Cooper, with music by Freddie Phillips. Multiple Injuries - Examination and the Essentials of Treatment (1963) Multiple Injuries - Examination and the Essentials of Treatment, which won the BMA Gold Award in 1964, was sponsored by Smith and Nephew. It was directed by Derek Stewart, with associate producer Terry Trench, photographed by Elmer Crossey, and edited by Jeanine Bradlaugh. |

|

|

|

Longlife (1963) and One Oil on the Farm (1963) The first BP-sponsored films that Trench worked on were Longlife [13 mins] and One Oil on the Farm, both written and directed by Derek Stewart, produced by Terry Trench, and photographed by Harold Case. Watch the whole of Longlife on BP Video Library. |

|

|

|

The Hidden Power (?date) Terry Trench edited The Hidden Power [20 mins], which was directed by Derek Stewart and photographed by Harold Case, and sponsored by BP. This black-and-white film concerns the manufacture and use of oil. Watch the whole of The Hidden Power on BP Video Library. |

|

|

|

Service to Industry (?date) Terry Trench was associate producer for Service to Industry [8 mins], which was directed by Derek Stewart, photographed by Harold Case, edited by Paul Shortall, and sponsored by BP. The film explains the lubrication-related products and services that could be provided by BP. Watch the whole of Service to Industry on BP Video Library. Independent Assessment (1964) Independent Assessment was directed by Derek Stewart, with associate producer Terry Trench, photographed by Rene Boeniger, edited by Jeanine Bradlaugh, with music by Leslie Williams, and sponsored by BP. |

|

|

|

By Hydrofoil to London (1964) By Hydrofoil to London [7 mins], about two hydrofoils travelling from the Netherlands to London, credits Terry Trench as associate producer. The music is by James Harpham. The film was sponsored by BP. Watch the whole of By Hydrofoil to London on BP Video Library. Report on British Hovercraft (1964) Report on British Hovercraft [13 mins] was another BP-sponsored film, directed by Gerald Bryant, photographed by Harold Case, associate producer Terry Trench, with a script by Leslie Mallory and music by Freddie Phillips. |

|

|

|

800 Mile Voyage (1964) 800 Mile Voyage [13 mins], about a hovercraft journey from Glasgow to London, was directed by Gerard Bryant, with associate producer Terry Trench, edited by Jeanine Bradlaugh, with music by Charles Zwar, and sponsored by BP. Watch the whole of 800 Mile Voyage on BP Video Library. |

|

|

|

Hovercraft in Holland (1964) Hovercraft in Holland [9 mins], about a demonstration of the Vickers VA-2 hovercraft, was directed by Gerard Bryant, with associate producer Terry Trench, photography by Harold Case, and sponsored by BP. Watch the whole of Hovercraft in Holland on BP Video Library. |

|

|

|

The Development of Endotracheal Anaesthesia (1964) The Development of Endotracheal Anaesthesia [15 mins] consists of Sir Ivan Magill being interviewed by Dr Cyril Scurr. It was the fourth in the BMA's series Medical History in the Making and was sponsored by the British Oxygen Company. It was directed by Derek Stewart, with associate producer Terry Trench, photographed by Harold Case, and edited by Jeanine Bradlaugh. Watch the whole of Development of Endotracheal Anaesthesia on YouTube. Man is a Builder (1964) Man is a Builder [19 mins] informed school leavers about careers in building. It was directed by Derek Stewart, edited by Terry Trench, with a script by Leslie Mallory, commentator Robin Hunter, and music by James Harpham. The film was sponsored by the National Federation of Building Trades Employers (NFBTE). The Right Knight (1965) The Right Knight, a partly animated allegorical film about contracts in the building industry, was directed by Terry Trench, with animation by Peter Sachs (a highly-regarded experimental animator), and a script by Leslie Mallory. It was sponsored by Bovis. 'The sponsor meant this to be a provocative film and this it certainly is. There are those who will say that the medieval battle scenes could have been dispensed with but the fact remains that they form an attractive aperitif that will assist the viewer to swallow the hard facts that follow.' (The Times, 17 May 1965) Any Old Thing (1965) Derek Stewart Productions made a few films for television, including Any Old Thing , made for ATV, in which antique shop owners talk about their business. It was directed by Derek Stewart, with associate producer Terry Trench, photography by Harold Case, and a script by Leslie Mallory. Frontier: The Hovercraft (1965) Frontier: The Hovercraft was a documentary made for television. |

|

|

|

Southend Story (1965) Southend Story [11 mins] was another BP-sponsored film, directed by Derek Stewart, photographed by Harold Case, with associate producer Terry Trench, and edited by Jeanine Bradlaugh. Watch the whole of Southend Story on BFI Player. |

|

|

|

Condor 1 (1965) Condor 1 [9 mins], about a 140-seater commercial hovercraft, was directed by Gerard Bryant, with associate producer Terry Trench and music by Elisabeth Lutyens, sponsored by BP. Watch the whole of Condor 1 on BP Video Library. |

|

|

|

The Ship and the Engineer (1965) The Ship and the Engineer [20 mins], about the work on an engineer on a pleasure cruiser with an oil-fired engine, was directed by Derek Stewart, with associate producer Terry Trench, photographed by Harold Case, edited by Jeanine Bradlaugh, with music by Leslie Williams, and sponsored by BP. Watch the whole of The Ship and the Engineer on BP Video Library. |

|

|

|

The Dawn of an Industry (1966) The Dawn of an Industry [25 mins], about the development of hovercraft, for which Terry Trench wrote the script and was associate producer, won first prize in Belgrade in 1967. It was directed by Gerard Bryant and Derek Stewart, photographed by Harold Case, edited by Jeanine Bradlaugh, with music by Albert Elms, and sponsored by BP. Watch the whole of The Dawn of an Industry on BP Video Library. |

|

|

|

|

|

Rolling Bearings and their Lubrication No.1: Taking the Load and No.2: Prevention - Not Cure (both 1966) Rolling Bearings and their Lubrication No.1: Taking the Load [13 mins] and No.2: Prevention - Not Cure [17 mins] were directed by Robin Cantelon, with Terry Trench as associate producer, and sponsored by BP. Watch the whole of Taking the Load and Prevention - Not Cure on BP Video Library. |

|

|

|

Hovershow '66 (1966) Another BP-sponsored hovercraft film, Hovershow '66 [13 mins], credits Gerard Bryant, Harold Case, Leslie Mallory and Terry Trench. It was sponsored by BP. Watch the whole of Hovershow '66 on BP Video Library. |

|

|

|

Hovercraft in the Canadian Arctic (1966) Hovercraft in the Canadian Arctic [15 mins] is a Derek Stewart Production made in collaboration with Crawley Films Ltd, Canada. The only credits are Terry Trench as associate producer, sound editor John Scott, and assistant editor Ben Harrison. It was sponsored by BP. Watch the whole of Hovercraft in the Canadian Arctic on BP Video Library. An Introduction to Acute Inflammation (1966) An Introduction to Acute Inflammation was sponsored by JR Geigy. It was directed by Derek Stewart, with associate producer Terry Trench, edited by Julian Cooper, with animation by Robert Lumley, and commentator John Glen. Counter Revolution (1967) The Yorkshire Film Archive holds a film called Counter Revolution [18 mins], made by Derek Stewart Productions, with associate producer Terry Trench, written and directed by Gerard Bryant, and photographed by Harold Case. The film shows the workings of the Grattan mail order company. See Counter Revolution listing on Yorkshire Film Archive. |

|

|

|

Hovercraft N4 (1968) Trench was associate producer for Hovercraft N4 [19 mins], directed by Gerard Bryant and sponsored by BP. Watch the whole of Hovercraft N4 on BP Video Library. |

|

|

|

Allegro (1968 or 1970?) Terry Trench was one of the credits for Allegro [14 mins], along with Derek Stewart, Jeanine Bradlaugh, Harold Case, Roger Davies, Bill Marshall, Brian Stevens, and Elisabeth Lutyens. This technicolor film concerns the use of car oil, and was sponsored by BP. Watch the whole of Allegro on BP Video Library. Together We Build (1969) Another NFBTE-sponsored film was Together We Build, directed by Gerard Bryant with Terry Trench as associate producer. According to The Times (28 July 1969): 'There is a human quality in the film which immediately communicates itself to the viewer'. |

|

|

|

Barbican (1969) The Corporation of London sponsored Barbican [23 mins], about the Barbican development of arts facilities and housing in the City of London. This film won an SFTA nomination, and was shown on general release in cinemas as a support film. It directed by Robin Cantelon, with associate producer Terry Trench, photographed by Harold Case, edited by Jeanine Bradlaugh, with music by Elisabeth Lutyens. Watch the whole film on YouTube: Barbican. John Grindrod in his blog Dirty Modern Scoundrel comments on Barbican as follows: 'With fantastic cinematography by Harold Case, a veteran of many short films on sixties subjects such as the hovercraft, direction by Robert Cantelon, and fruity dialogue written by Frank Harvey ('Now it's all women in mini-skirts!'). Perhaps the most interesting contributor is the composer, Elisabeth Lutyens, daughter of architect Edwin Lutyens. Despite a career composing hundreds of pieces of modern classical music, she remains more well known for creating horror movie scores for Hammer and Amicus, and films such as Dr Terror's House of Horror, The Earth Dies Screaming and Theatre of Death.' Pain at Night (1970) Pain at Night was directed by Derek Stewart, with Terry Trench as both editor and associate producer, and photographed by Harold Case. It was sponsored by Merck Sharp and Dohme. Soft Tissue Injury (1970) Soft Tissue Injury was also sponsored by Merck Sharp and Dohme. It was directed by Derek Stewart, edited by Terry Trench, and photographed by Harold Case. The Build Up (1970) The Build Up is a management training film about avoiding strikes, sponsored by the National Federation of Building Trades Employers. It takes the form of a story, in which failure of communication is one of the main causes of a strike. The film was written and directed by Gerard Bryant, with Terry Trench as editor and associate producer, and photographed by Harold Case. Gerard Bryant recalled that, during the making of The Build Up, 'Terry objected strongly' to one particular line 'on the grounds that the film should maintain complete impartiality between management and labour. However, the producer and myself insisted on the line being retained, as we both felt it was completely in character and right in context. Terry gave in, but he didn't like it one little bit. I have told the story at length, because I feel it is a good example of his fairness and integrity as a film maker.' Materials for the Engineer (1970) After the closure of the Crown Film Unit, the Central Office of Information commissioned films from independent producers. Materials for the Engineer was sponsored by the COI and the Department for the Environment, and gives information about materials such as glass fibre board, titanium alloys and yttrium iron garnet. The film was directed by Derek Stewart, with associate producer Terry Trench, photographed by Harold Case, and with Gerry Fallon as sound editor. |

|

|

|

Project Horizon (1971) In 1971, Terry Trench was associate producer and editor for Project Horizon, on which he worked with director Gerard Bryant for the last time, and which included music by James Harpham and photography by Harold Case. It is a documentary about the design and building of a tobacco factory in Nottingham, and was sponsored by John Player, Bovis and Arup. Watch the whole of Project Horizon on 'People at Players' website. General Practice and the Future (1972) General Practice and the Future was sponsored by Geigy Pharmaceuticals. It was directed by David Eady, edited by Terry Trench, and photographed by Harold Case. Clean Beaches (1973) Terry Trench's final film was Clean Beaches, which shows the effect of oil spillages on beaches, sponsored by BP. It was directed by Derek Stewart, edited by Terry Trench, and photographed by Harold Case, with a script by Frank Harvey. Watch the whole of Clean Beaches on BP Video Library. |

|

|