Do you remember it - or weren't you there?

Curated by Cally Trench and Philip Lee

Catalogue essayDo you remember it - or weren't you there?

|

Performance art is like life. Unlike theatre, performance art is rarely repeated. There is usually only one chance to be there. Like a journey, a meal, a party, or a wedding, you miss it if you aren't present. You may see the video or the photographs, you may be sent a slice of cake, or get an email telling you about it, but you still missed it and you can never change that. |

|

If you were there, what are you left with? You will have a memory of the event, and maybe some photos on your mobile phone, and you may be able to describe it to someone else, but you can't go back and watch it again. Performance art doesn't exist as an object. The work is not a painting, a drawing, a photograph, a film, a print or a sculpture. It does not exist beyond the time of its happening. Performance art is live: it exists only for a specific time in a particular place. As Peggy Phelan writes: 'Performance's only life is in the present. Performance cannot be saved, recorded, documented, or otherwise participate in the circulation of representations of representations: once it does, it becomes something other than performance.' (Phelan, 1993, p146) For performance artists, one choice is to insist on performances not being documented, and to ensure that the performance lives on only as a memory, a story passed from person to person. This is performance art as myth. During the 1970s, Anne Bean did not allow documentation; her performance art was not documented and was preserved only in the memories of those who saw her work. Others have done similarly. Laurie Anderson wrote in her foreword for Rosalee Goldberg's Performance Art since the 60s, that early in her career she was proud that she did not document her work, preferring for it to be recorded 'in the memories of the viewers - with all the inevitable distortions, associations and elaborations.' (Anderson, 1998, p6) However, for most performance artists, some kind of record is important, both to disseminate the event to a wider audience and to allow discussion of it. As Erika Fischer-Lichte points out: 'Such documentations rather create the conditions of possibility to speak about past performances at all.' (Fischer-Lichte, 2008, p75) Some artists choose to exercise extreme control over the dissemination of their performances. Marina Abramovic made a decision to choose one emblematic photograph of each performance: she says, 'I made sure to document [Thomas Lips (2005)] in the best possible way. I had three professional photographers photograph this piece from every possible angle, and I chose just one photo from all the material to represent that piece.' (Abramovic, 2008, p.38) In these days of mobile phone cameras and YouTube, keeping control of images of a performance may be a lost cause. Indeed some performance artists make use of publically available footage from mobile phones; Richard DeDomenici's lecture Propaganda includes YouTube videos of his public interventions. One approach we have tried is to offer souvenir postcards to those who attend performances; the images are specially prepared, printed on watercolour paper, and signed. They are reminiscent of the signed postcards of Victorian music hall artistes, such as Cally's grandfather's first wife, Belle Bilton (later Lady Dunlo). The postcards are pleasing objects that are both souvenirs and minor works of art. |

|

Other artists also choose to give out souvenirs which act as a trigger for memory. Silvia Ziranek often gives out badges. Another experimental approach we have tried is to make silent timelapse films. These compress a performance into a minute or two. They do not pretend to show the performance in real time, but flash past like a memory. They are also beautiful and engaging films in their own right. A further choice that we made is not to exhibit documentation, films or photographs, in an exhibition after a performance. This is partly because we do not want to give art status to work that is purely documentary. However, a more significant reason is that we do not want to create the feeling in visitors that they are being shown that they have missed something. Instead, we started making performances to camera to create films that are art objects in their own right, and these are what stay in an exhibition. This exhibition, Do you remember it - or weren't you there?, shows the results of another experiment. In 2010, we invited some artists and writers to make work in response to one or more of our performances. We asked that this work should not be documentation, but art in its own right, part of the artist's usual practice. Our view was that this would be a kind of ekphrasis. In rhetoric, ekphrasis is a way of describing an event or object so that listeners feel its emotional impact. The term is also used of writing that describes and conveys the feeling of a work of art. One famous example is Landscape with the Fall of Icarus (1962) by the American poet William Carlos Williams, a poem which describes and recreates in words some of the feelings and ideas depicted in the painting of that title attributed to the 16th-century painter Pieter Brueghel the Elder. It could be argued that all writing about art, including reviews and critiques, are ekphrastic; however, we decided to focus on the idea that ekphrasis could convey the emotion of a work of art. We also wanted to use a broad definition which would allow ekphrasis to include any art form, not just writing, as a way of conveying the nature of another work of art, in this case our performances. We have been collaborating on performances since 2009, a working-together that involves the sharing of ideas, planning and performing. The performances in 2010 and 2011 that most of the artists saw involved Philip (naked), Cally (clothed), clay slip and a blindfold. It was important to us and to the artists that their work should not simply document a performance or be something separate from their normal art practice. |

|

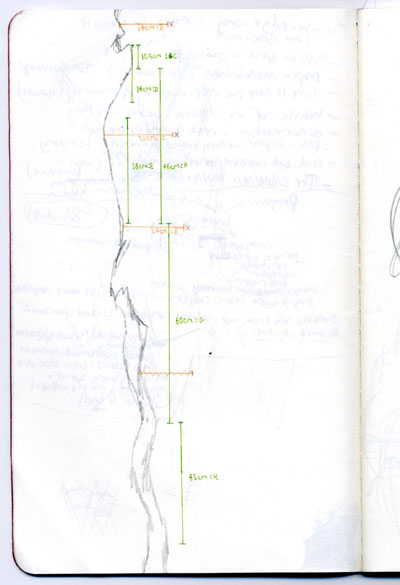

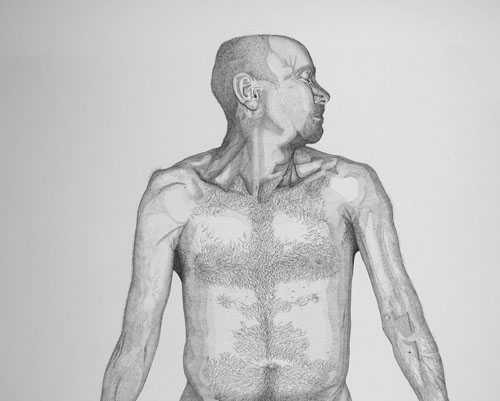

Mary Yacoob wrote: 'I tried to connect my experience of the performance with my wider practice, which is often about adapting scientific or architectural methodologies and visual systems, sometimes in absurdist contexts such as fantasy urban design or domestic minutia. On this occasion I was trying to connect different ways of measuring the body: the performer's own measurements of his body; my attempt at a life drawing whilst the performer is in motion; and classical notions of harmonic proportions with regard to the body and architecture. In a way, all these are subjective ways of filtering our perceptions. Initially I 'corrected' my life drawing with Philip's measurements of his body, seeing how close or far my sketch was to Philip's measurements. Then I combined these two systems with the perceived ideal proportions of man found in Da Vinci's drawing Vitruvian Man.' Some of the work in Do you remember it - or weren't you there? was created during an actual performance. It becomes evidence of the witnessing of the event, and a proof of presence. |

|

Ingrid Jensen's sketchbook, with its lively drawings of Philip, and her larger muslin drawings, some of which are marked by splashes of clay, are immediate and memorable responses to a performance. Each performance is different, and the venue and the audience also have an impact on the work of the artists. Ingrid Jensen comments that: 'During the Brick Lane performance I was much concerned about Philip freezing and shaking in a vulnerable foetal position on the cold concrete, surrounded by rather brutal and bloody painted torsos by Benjamin Cohen. He was also surrounded by an audience that partly seemed to be viewing him, appreciatively, as spectator meat. Being alive is a precious and precarious state.' |

|

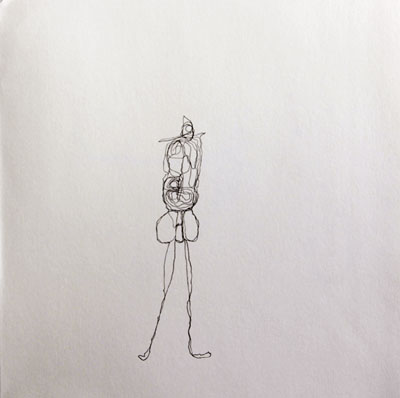

Jane Grisewood also made work during the performances, but in a different way. Using two different kinds of pencil, one to represent Philip and one Cally, she recorded the movements we made, like a human seismograph, in her Mapping Blindfold Slip drawings. As performers it was comforting to know that we were being watched so carefully, that we had an audience. Philip wrote: 'The Blindfold Slip performances were the first time I have not been able to see what the audience was doing and interact with them during a performance. I did not anticipate that sightlessness would affect me so much; it made me feel very anxious. Was I being ignored? Had they all gone? Were they laughing at the performance and particularly at me? What is going on? At times I felt miserable. And yet, I would think, at least Jane is with me; at least Jane is watching. Jane is registering my every move, my every breath. I am not alone; at the very least I am performing for Jane, so I will keep going.' Silvia Ziranek's writing is a spontaneous personal set of observations and responses during a performance; these are sparse, poetic and evocative. Marco Cali recorded comments and conversations among the audience during a performance; for these Marco acted as both the net to catch the words and the filter to organise them, in Script for a blind performance I and Questioning Poem. By contrast, some of the work in Do you remember it - or weren't you there? is concerned with not being there, with absence and missing the event, as well as with presence. Alison Carter Tai's text, The Remarkable Philip Lee, is a detailed diary of her thoughts and feelings before seeing a performance, followed by an account of her much-anticipated encounter with one. Lydia Julien was unable to come to the performances, and she asked a friend, Claire Norman, to attend one for her and take photographs. Claire's chosen photograph, Document 2011, depicts the performance through the lens of another camera, reflecting her feelings of alienation and distance. Lydia's photograph of herself, naked and with her legs dusted with plaster, i wasnt there, she was, show by contrast her desire to step into the performance that she missed, to feel what she didn't experience. Some of the work in this exhibition resulted from thoughts and memories of the performances, synthesised over time. |

|

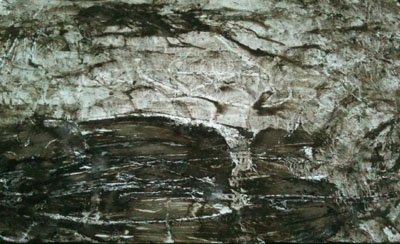

Tony Moody's painting, Rebirth of the Universal Child (2010), arose out of a process of letting 'the experience sit on the system, to make no notes/drawings, and then contemplate and use those distilled thoughts'. Lorraine Pepper's Blindfold Slip: A Response is a lucid and poetic description of a performance recollected, but conveyed with immediacy. For some artists, there was a desire to empathise with Philip's emotions or physical feelings. The performances involve hardship and endurance. |

|

Steve Perfect asked himself how he would feel 'if I chose to appear naked before friends and strangers in some kind of performance', and his six drawings explore this identification. |

|

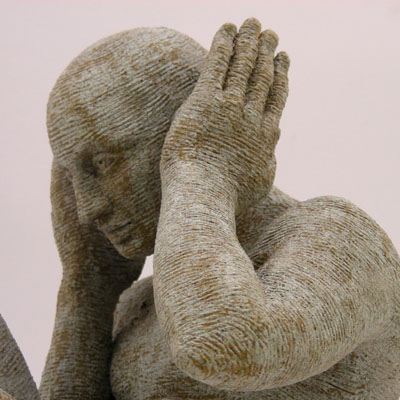

Judy Goldhill thought about the 'physicality of Philip', and her Reed Paintings were an attempt to recreate Philip's 'waterlogged corporeality'. Ann Rapstoff, who will be performing Energy Channel at the private view on 30 January 2013, also empathises with Philip; she writes: 'This will be the first time I have worked in response to Philip's work; I am excited to have the opportunity to explore this dialogue. As an artist who works with performance I have a strong empathic response to the vulnerability of the lone figure covered in the slip liquid. The sense of exposure and erasure of the skin is unsettling and yet liberating. One can practice a performance or allow the process to unfold; I plan to do the latter on the opening night. I want to feel the vulnerability of being unprepared for what might happen, to feel a lack of control. I want to explore the energy of being a mirror in the present to the work but also a witness.' |

|

One of Philip's concerns is how to convey the liveness of a performance in another form. His own work in this exhibition aims to animate still images, and to make the stationary move. Two, a flipbook and a phenakistoscope, use persistence of vision and techniques of early cinema to create the illusion of motion. The third, a one-fold book, presents two images that cannot be seen simultaneously; the viewer can alternate between the two, creating a primitive sense of motion. Sophie Loss's work also makes the two-dimensional paper three-dimensional, bringing it to life. It emerges from a record of a performance in her possession, a photograph of Philip naked. Her work has 'surface and absence, twists, curves, and shadows', making it like a memory. |

|

Zahed Tajeddin's work emerged from the confluence of two inspirations, our performance and a poem. The result is enigmatic and beautiful. |

|

Helen Udal's film, War Angel, also combines two sources of inspiration. For her, the footage of Philip covered in clay had the 'visual and emotional resonances of a man suffering from a post-war trauma' She combines this footage with a poem by Steve Carlsen, a veteran of the Vietnam War. For some artists, the project provided the challenge of how to say something about one art form in another art form. Alison Carter Tai comments that Alan Prosser responded 'in the form of musical notes rather than notes in words, as an exercise in his own self-discovery in describing art through music, I feel, as well as paying his own tribute to your bravery and ingenuity in creating the live performance'. |

|

Cally Trench's work in this exhibition arises from her belief that the central matter of the performances is Philip's naked body. What we are not usually allowed to do is deeply tempting. We want to look at naked bodies: to compare, to feel excited, to see what is usually hidden. Cally is aware that, while she is co-author of the work in which she performs with Philip, she is usually invisible. The viewers see Philip. His nakedness makes him visible, and the clay slip gives people permission to look at him. Her clothes make her invisible, and she is mostly invisible in this exhibition. Cally's drawings also give people permission to stare at Philip's naked body; the extraordinary detail of the drawings reveals every wrinkle, scar and blemish. We are very grateful to these artists, writers and musician for making these works of art, works in their own right, but which also convey, in our opinion, something of the emotion and physicality of our performances. Christopher Bedford, in his 2012 essay, The Viral Ontology of Performance, proposes that performances have an afterlife, which is as significant as the performance itself. He argues: 'that art history, art criticism, art practice, and even popular journalism all participate in the extension and reproduction of performance art in the public sphere and are, therefore, in the absence of a conventional 'object', as potent and performative as the originary work.' (Bedford, 2012, p. 77) Bedford suggests that the performance is the starting point of a 'viral chain'. In our opinion, conventional documentation and description do not have the potency of the original performance, and lack its immediacy and viscerality. However, the works in this exhibition are not documentation and do indeed form part of a potent afterlife. This is because they are also works of art, and so have the power to move, engage, and transform the viewer. This is ekphrasis. Cally Trench and Philip Lee Abramovic, M., STOKIC, J., (2008). Conversations with photographers; Marina Abramovic speaks with Jovana Stokic. Madrid: La Fabrica. Anderson, L., (1998). This is the time and this is the record of the time. In: Goldberg, R., (1998). Performance: live art since the 60s. London: Thames & Hudson Bedford, C., (2012). The viral ontology of performance. In: Jones, A., Heathfield, A., (eds.). Perform, repeat, record: live art in history. Bristol, UK, Chicago, USA: Intellect Fischer-Lichte, E., (2008). The Transformative Power of Performance. London: Routledge. Phelan, P. (1993). Unmarked: The Politics of Performance, London: Routledge. Do you remember it - or weren't you there? features work by Marco Calí, Alison Carter Tai, Judy Goldhill, Jane Grisewood, Ingrid Jensen, Lydia Julien, Philip Lee, Sophie Loss, Tony Moody, Claire Norman, Lorraine Pepper, Steve Perfect, Alan Prosser, Ann Rapstoff, Zahed Tajeddin, Cally Trench, Helen Udal, Mary Yacoob, and Silvia Ziranek, and is curated by Cally Trench and Philip Lee. |